This column first appeared March 21 on Misrule of Law.

My law school years (1977-80) at the University of Texas were, in hindsight, close to idyllic. I loved my first-year professors, tuition at UT was dirt cheap, Austin was a wonderful place to live, and I reveled in the “college town” ambience, which was new to me. (Prior to arriving at UT, I had never attended a college football game. During my first year—when the Longhorns went undefeated in the regular season and Earl Campbell won the Heisman Trophy–I had season tickets on the 50-yard line at UT’s gigantic Memorial Stadium, for a pittance that even a broke law student could afford.) The post-game victory spectacle—honking horns on the Drag and the Tower lit up in orange—formed indelible memories.

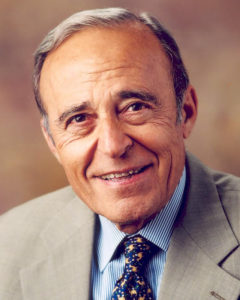

My biggest regrets were that I didn’t get a chance to take Charles Alan Wright for Federal Courts (drawing Bernie Ward instead), and never experienced Lino Graglia in the classroom. My first-year Constitutional Law professor was Jerre Williams (later appointed to the Fifth Circuit), and Lino was visiting at the University of Virginia during 1978-79, forcing me to take Antitrust from a forgettable visiting professor instead. (Since Lino arrived at UT in 1966, over 50 years ago, he has mainly taught Con Law and Antitrust.) Lino is anything but forgettable; the May/June 2011 issue of Alcalde featured him as one of UT’s “Great Professors.” Despite Lino’s reputation as an entertaining and effective lecturer, which made his classes very popular (at least in the pre-snowflake era), I am—sadly–not among the legion of his former students.

Nevertheless, I have always felt an affinity for Lino, whom Wikipedia describes as “one of the most conservative legal academics in the United States.” Texas Monthly’s Paul Burka once described him as the “most controversial law professor in America.” Both of those statements reveal more about the cloistered, insular, and leftist tilt of the legal academy than they do about Lino, who is a mainstream (albeit outspoken) conservative. Many law professors succumb to liberal Groupthink, and the few who are center-right tend to conceal their contrarian views to avoid confrontations. Not Lino. He is uncompromisingly honest, and never bashful, a combination that often puts him in a spotlight that others might find uncomfortable. The unflappable Lino takes it in stride—even thrives on it.

For as long as I can remember, the indefatigable Lino has been the patron saint of conservatives at UT law school, serving as faculty advisor or sponsor for various conservative student groups and publications (including the Texas Review of Law & Politics, founded in 1996), and offering to speak, debate, or pen an op-ed whenever controversial issues required a conservative voice. Lino defines the word “stalwart.”

Although I was never a student of his, we have stayed loosely in touch over the years, and I always enjoyed hearing him speak at Federalist Society events and reading his essays in National Review, Commentary, and the Wall Street Journal, as well as various scholarly publications. I see more of Lino now that I moved back to Austin—at the annual Texas Review of Law & Politics banquet, for example–and occasionally trek down to the law school to visit him in his cluttered sixth floor office. At 88, he has slowed down, no longer playing tennis, snow skiing, or taking long bike rides. But Lino is still Lino: gregarious, affable, self-effacing, jocular, opinionated, and (sometimes) blunt.

I realized that Lino is overdue for a profile. Here it is.

For a man who has faced significant professional disappointments during his career—being unfairly rated “not qualified” by the American Bar Association in 1985, foiling his potential nomination by President Reagan to the Fifth Circuit, and being denounced by UT administrators and most of his faculty colleagues in 1997, for making ostensibly “insensitive” comments about academic differences among various ethnic and racial groups—Lino exhibits considerable equanimity and discusses the setbacks with no apparent rancor. He is not a bitter man.

His only professional “regret,” he insists, was turning down an offer during the Reagan administration to become the First Deputy Solicitor General (serving under SG Rex Lee), a decision he acknowledges was influenced by his pique at not being offered a position at DOJ heading the Civil Rights Division–and also by his reluctance to disrupt his family’s contented life in Austin.

Contrary to his media caricature as a troglodyte, Lino is quite tame. He is personable, even garrulous. He describes himself as a libertarian. He has been happily married to his wife, Kay, for over 60 years. A nature lover and avid hiker, he has visited nearly all of the national parks and climbed Longs Peak in Colorado (elevation: 14,259 feet) a half-dozen times. One of his closest friends on the UT faculty is the liberal labor law scholar, Jack Getman, a fellow New Yorker and CCNY graduate.

Nor is Lino a misogynist. He grew up with three sisters (making him, he quips, “the last of the male Graglias in the Western Hemisphere”).

Lino and his wife, Kay, have lived in the same house in West Austin since they arrived in Austin in 1966, and raised three daughters there (of whom he is quite proud). One is a lawyer, one is a pediatrician, and one teaches English literature in high school. Lino is also very proud of his wife, who was a classmate of his at Columbia Law School (where they served together as editors on the law review). Kay was a brilliant student who went to college at Cornell, attended Columbia on a full scholarship, made law review, and later clerked for Warren Burger on the D.C. Circuit and practiced law at Covington & Burling, one the nation’s most prestigious firms.

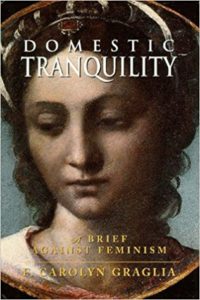

As she discusses in her remarkable 1998 book, Domestic Tranquility: A Brief Against Feminism, Kay (who was several years ahead of Ruth Bader Ginsburg at Columbia Law School) was offered a job at Sullivan & Cromwell, a leading Wall Street law firm, dispelling the myth of widespread sex discrimination in the legal profession during the 1950s.

There was certainly anti-Semitism on Wall Street, which in the 1950s was dominated by WASPs (likely explaining any obstacles Ginsburg faced), but the same ethnic biases also hindered the prospects of Italian-Americans with ethnic surnames, such as Lino. We have difficulty today conceiving of anti-Italian-American animus, but it was a reality 50 years ago. Recall that no Italian-American served on the U.S. Supreme Court prior to the appointment of Antonin Scalia in 1986, long after Thurgood Marshall broke the Court’s color barrier in 1967.

Even though Lino had an excellent academic record at Columbia Law School, he did not receive a summer intern or permanent offer from a Wall Street firm, but was very fortunate to be hired, along with Kay, in the Department of Justice’s newly-created Honors Program in Washington, D.C.

Despite being on the receiving end of enough enmity and vituperation to scald most men, Lino is not angry or scornful, or even disillusioned. Rather, he is a happy warrior—often mischaracterized and poorly understood—still engaged in the intellectual battle. Far from a rigid ideologue, Lino voted Democrat until he was in his 40s. He voted for Adlai Stevenson twice, picked JFK over Nixon in 1960, favored LBJ over Goldwater in 1964, and Hubert Humphrey over Nixon in 1968. Not until the Democrats nominated ultra-liberal George McGovern for President in 1972 did Lino make the switch to the Republican Party. As Ronald Reagan used to say, he didn’t leave the Democratic Party; the Democratic Party left him.

Looking back at his half-century of teaching, Lino considers himself fortunate. He grew up during the Depression in a lower-middle class area of Brooklyn (the Bedford-Stuyvesant section). His mother never got past the sixth grade, and his father died when he was 16. During high school (at the selective, all-male Brooklyn Tech), he worked part-time setting pins at a bowling alley–before the advent of mechanical pin-setters–hopping from one lane to the next to avoid being struck by bowling balls. Little did he know it, but this was good experience for a future controversialist—dodging dangerous projectiles. Lino was bright, enjoyed school, and was a good student. He had to compete in order to excel, because his classmates—in both high school and college—were overwhelmingly smart, upwardly-mobile children of Jewish immigrants.

After high school, he recalls with obvious fondness attending the City College of New York in Manhattan, tuition-free, commuting from his home in Brooklyn on the subway for ten cents a day—a nickel each way. He chose City College over Brooklyn College—the only two schools he applied to—because taking the bus to Flatbush (where Brooklyn College was located) would have been more difficult and less reliable.

Speaking of City College, Lino told an interviewer in 2009 that “I just loved it. I kept thinking what a great country it is. They let you come here free and listen to these people and take these courses.” [Tarlton Law Library Oral History Series No. 13, at p. 3 (an excellent biographical overview).] At City College, Lino thrived in all subjects except first-year physics. His favorite subjects were political science, economics, and philosophy. Lino loved the academic environment and, as college graduation approached, considered pursuing a Ph.D. in order to become a teacher. He realized, however, that financial considerations precluded that course of action.

In the 1950s, working class Italian-Americans with widowed mothers needed to get a job and support themselves, as his uncles frequently reminded him. In the Sicilian culture, going to college was viewed as a waste of time. Without a specific career plan, Lino had gone to college “for the sheer joy of it,” but the joy was about to end. [Id. at p. 5.]

Fate intervened. Learning that one of Lino’s old high school friends was going to Yale Law School after college graduation, Lino’s mother turned to Lino and said “You like to talk, why don’t you go to law school?” [Id. at p. 6.] Thus, at his mother’s urging, as a college senior an unfocused Lino abruptly decided to attend law school, taking the LSAT at the last minute. He had no particular desire to be a lawyer; he just enjoyed the intellectual stimulation of the classroom. So, he applied to Columbia Law School and was accepted, paying for his schooling (which cost a mere $600 a year in tuition at the time!) with the help of a small scholarship and by working as a machinist in a defense plant during the summer. How ironic that a future legal scholar went to law school “by default.” [Id. at p. 9.]

Lino loved law school, and especially Columbia’s all-star faculty, which included Herbert Wechsler, Walter Gellhorn, and Milton Handler. During his first year, he continued to commute from Brooklyn on the subway for ten cents a day round trip. (Columbia was just two stops past CCNY on the subway.) Only when he made law review and needed to spend far more time on campus did he leave home and get an apartment closer to school.

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, has long been one of the nation’s premier law schools. In 1951, when Lino enrolled, only Harvard and Yale had a comparable national reputation. Although proximity and happenstance combined to attract Lino to become one of the 290 students in the Class of 1954, Columbia Law School had an august history: Its graduates founded several prominent Wall Street law firms, and have served with distinction on the bench, including Chief Justices Charles Evan Hughes and Harlan Fiske Stone, and Associate Justices Benjamin Cardozo, William O. Douglas, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Many Columbia Law alumni have distinguished themselves in the legal academy, including Herbert Wechsler, Charles Fried, Louis Lusky, and Walter Gellhorn. Perhaps no graduating class—at Columbia Law or any other school–yielded a larger crop of prominent law professors than Columbia’s Class of 1954, which included William K. (“Ken”) Jones (Columbia), Warren Schwartz (Georgetown), Geoffrey Hazard (Yale), Yale Kamisar (Michigan), and Robert Pitofsky (Georgetown).

As it turned out, after Lino graduated in 1954 and had practiced law for a dozen years in Washington, D.C. and New York City, Lino would be joining those illustrious ranks. Lino’s former Columbia classmate, Ken Jones (who had been editor-in-chief of the law review and was then teaching at Columbia Law School), encouraged Lino—then working on Wall Street–to consider a teaching position. At Jones’ urging, Lino attended the AALS “meat market” in Chicago, where he met with a contingent from UT including Page Keeton, Charles Alan Wright, and Corwin Johnson (my first-year Property teacher). Keeton offered him a position, and in 1966 Lino moved his family from New Jersey to Austin, where—excepting a few visiting positions—he has been ever since.

At UT, Lino realized his longtime dream of earning his living in the classroom. One of the many ways legal education has changed over the past 50 years is the increased emphasis on writing—over teaching—by law professors. That, and dramatically-higher salaries for faculty and administrators. (Lino started at UT for $14,000/year, plus $3,000 for teaching summer school!)

Lino’s first five years at UT were uneventful. He stayed busy teaching Constitutional Law and Antitrust, including during the summer. He became a full—tenured—professor in 1968. His first published article, entitled “Special Admission of the ‘Culturally Deprived’ to Law School,” appeared in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review in 1971 (dated 1970). The article dealt with a trend that began in the late 1960s at UT and other law schools: affirmative action in law school admissions. Lino was opposed to lowering standards for certain “disadvantaged” groups, on the grounds that doing so would discriminate against other applicants, stigmatize the intended beneficiaries, and likely prove ineffective if unqualified or unprepared students were expected to compete with their academically-advanced peers.

The article was one of the first critiques of affirmative action published in a law review. (Penn only agreed to publish Lino’s article if it were accompanied by a rebuttal.) Lino’s concerns presaged economist Thomas Sowell’s later work, and UCLA law professor Richard Sander’s “mismatch” analysis. Prescience, however, is not rewarded in legal academia if it debunks an article of liberal faith, and even in 1970 the Left was committed to the goal of end-result equality among society’s “victim” groups.

Lino, characteristically, cut to the heart of the issue when he pointed out that “Achievement of proportional representation of different groups is not a proper goal of higher education…. Society needs the best lawyers it can get, regardless of racial or ethnic derivation.” By opposing affirmative action, the iconoclastic Lino had challenged the emerging orthodoxy of identity politics. Lino was not deterred by the unpopularity of his stance among his colleagues, because he was convinced that he was right. The die was cast.

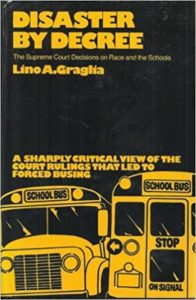

Dean Page Keeton had given Lino a research leave in 1971, which Lino intended to use to write a long article or book on the First Amendment. But when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its first busing decision that year in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), an outraged Lino decided he had to write about busing instead. The project took three years. What began as an intended article morphed into an encyclopedic book, published by the Cornell University Press in 1976, entitled Disaster by Decree: The Supreme Court Decisions on Race and the Schools. Lino had now taken on two of the legal academy’s most sacred cows, making him a pariah to many of his colleagues. Rather than harming his career, however, Lino’s notoriety led to invitations to speak and debate, and even television appearances. Lino testified before Congress several times, beginning in 1977.

In conservative circles, Lino was becoming a celebrity, and he enjoyed the spotlight.

Court-ordered busing proved to be a disastrous social experiment, causing massive white flight from many affected school districts throughout the nation, exacerbating rather than ameliorating racial separation in many cities. Austin probably owes Lino a debt of gratitude for his role in persuading the U.S. Supreme Court to reject the massive busing plan for Austin schools ordered by the Fifth Circuit, the first time the Court failed to require busing in a southern city. As a result, Austin survived the busing wars relatively unscathed.

By the time the Supreme Court trimmed Swann’s sails in Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974), the damage had been done. Hampered by widespread public opposition–sometimes quite fierce–court-ordered busing continued to fall out of favor, and was curtailed significantly by the Rehnquist Court in the early 1990s. In 2007, the Roberts Court prohibited altogether the use of racial assignment plans to maintain racial balance in public schools.

The Court had come full circle since Swann. Lino’s criticisms of court-ordered busing were vindicated. Again, however, prescience is not regarded as a positive attribute if it entails debunking a liberal shibboleth. Rather than a prophet, Lino was viewed by the liberal establishment as a truth-telling trouble-maker—a heretic.

The Court retreated from court-ordered busing, due in large part to Lino’s evisceration of Swann and later decisions. However, in Bakke (1978), Grutter (2003), and Fisher (2016), the Court condoned racial preferences in higher education admissions, perpetuating a contentious and divisive racial spoils system that continues to this day. Prior to Grutter, UT litigated and lost a bitterly-fought federal court challenge to racial and ethnic preferences in admissions in the Hopwood v. Texas (1996) case, in which the Fifth Circuit ordered UT to cease using race and ethnicity as a factor in admissions. The Supreme Court denied cert. Once again, even though Lino was vocally aligned with the “winning” side of that case, harkening back to his Pennsylvania Law Review article decades earlier, his prescience made him more of an outcast.

Similarly, the wildly-exaggerated controversies, bordering on hysteria, that sometimes threatened to engulf Lino—such as his public comments pointing out that certain ethnic groups emphasize academic achievement more than others, or that children raised in poverty without an intact two-parent family face disadvantages that are often difficult to overcome—are based on indisputable facts that liberals wish to ignore because they call into question the wisdom of progressive policies and Great Society programs. Ironically, when taboos are involved, stating the unwelcome truth provokes the most vociferous reaction.

Lino became a figure of national controversy in September 1997, when the Rev. Jesse Jackson came to Austin to denounce him as “a moral and social pariah” for pointing out that the reason for affirmative action is that too few Blacks and Mexican-Americans meet the ordinary admissions standards at selective institutions of higher education. Jackson later invited Lino to debate him on the topic on his national TV program, after which he complimented Lino on his performance and asked him to “keep in touch.” The happy warrior had made an unlikely friend.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Lino found an ally in Robert Bork as they both criticized judicial activism and championed a more restrained role for federal judges. Writing in a variety of publications, ranging from the Harvard Law Review to National Review, Lino pungently denounced judicial imperialism as a usurpation of constitutional democracy. As he memorably stated in a 1984 NR article, “The assumption, almost universal among academics, is that the American people are not to be trusted with self-government and are much in need of restraint by their moral and intellectual betters.” Lino repeated this theme in dozens of speeches and articles throughout the 1980s and 1990s, becoming—with Bork–the leading proponent of judicial restraint. When the Federalist Society was founded in the early 1980s, Lino became a mainstay of Federalist Society programs.

Along with Raoul Berger (author of the 1977 book Government by Judiciary) and Robert Bork, Lino was one of the principal advocates of the “strict construction” or “originalist” critique of the Warren and Burger Courts’ activist approach to “living constitutionalism.”

In 1992, Lino wrote an article in the Stanford Law Review defending Bork from an attack by then-Judge Richard Posner, entitled “‘Interpreting’ the Constitution: Posner on Bork.” Some of his other notable publications include an article on religious liberty in the Georgetown Law Journal (1996); a critique of Lawrence v. Texas (2003) (which recognized a constitutional right to engage in homosexual sodomy) in the Ohio State Law Journal (2004); a review of Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III’s book Cosmic Constitutional Theory (2012) in Constitutional Commentary (2014); a 2016 essay entitled “Rethinking Judicial Supremacy,” also in Constitutional Commentary; and a critical review of Georgetown law professor Louis Seidman’s book On Constitutional Disobedience (2012) in the Texas Review of Law & Politics (2015), pointing out that the problem of loss of democracy is not caused by the Constitution, as Seidman argued, but by the Court.

One of Lino’s best articles, the lead chapter in a book edited by Robert Bork that was published by the Hoover Institution in 2005, “A Country I Do Not Recognize”: The Legal Assault on American Values, has unaccountably drawn little recognition. Lino’s article, entitled “Constitutional Law without the Constitution: The Supreme Court’s Remaking of America,” is a summation of the themes and arguments he and Bork had made for decades. In his Introduction, Bork states that “Graglia’s comprehensive indictment is entirely justified. The contest is one between democracy and oligarchy, and for half a century the oligarchs have been winning.” I highly recommend it. The book is still in print. Buy a copy; you won’t be disappointed.

Lino describes himself as a Thayerian, after James Bradley Thayer, whose influential article, “The Origin and Scope of the American Doctrine of Constitutional Law,” appeared in the Harvard Law Review in 1893. In Thayer’s view, the Supreme Court’s role is to police the boundaries of the Constitution’s grant of power to the executive and legislative branches, not to interfere with the exercise of executive or legislative discretion within those boundaries. As Lino is fond of pointing out, much of “constitutional law”—that is, the decisions of the Supreme Court—has little or nothing to do with the text and history of the actual Constitution. The Supreme Court, particularly since the middle of the 20th century, has forgotten how to defer to the political branches.

After 50 years in the academic arena, and all the books, articles, and controversies, what more is there to say? Plenty, it turns out. Even at age 88, Lino comes to the office every day, poring over legal periodicals and advance sheets to find new things to argue about. He is still writing, corresponding, and holding forth with visitors. Last year, Lino had a long article in the Wake Forest Law Review on the First Amendment implications of criminalizing threats, entitled “The New Law of Threats: But What if the Defendant is Not a ‘Reasonable Person’?”. On a recent visit, Lino spoke of a couple of new articles he is working on. The discourse never ends.

Lino doesn’t like to discuss his “legacy.” With many thousands of former students, he is recognized wherever he travels, even abroad. Now in its third decade, the Texas Review of Law & Politics, the student-run journal for which he serves as faculty advisor, continues to grow in influence. The annual TROLP banquet, attended by many of the nation’s leading lawyers and judges, honors the most courageous TROLP member with the aptly-named “Lino Graglia Award.” Lino is understandably disappointed that UT law school no longer allows him to teach Constitutional Law, because his unfashionable views of the 14th Amendment are objectionable to some minority students. In today’s climate of political correctness, timorous law school administrators cower in fear of charges of “racism,” however unfounded. As recently demonstrated by the shameful ostracism of Professor Amy Wax by the University of Pennsylvania Law School, law school deans are easily mau-maued.

But Lino takes the disappointment in stride. Lino’s motivation for teaching is the joy that he gets from the academic give-and-take. For 50 years, Lino has enjoyed doing battle in the intellectual arena. The scrappy Italian-American from lower-middle class Brooklyn, who couldn’t believe his good fortune at being able to attend City College for free, still approaches being a law professor at UT as a blessing.

And so the happy warrior soldiers on.